Hey peptide adventurers and science fanatics! Kai Rivera here, diving headfirst into one of immunology’s most fascinating plot twists: molecular mimicry. Ever feel like your immune system is playing a high-stakes guessing game where the wrong answer means friendly fire? That is exactly what can happen when tiny peptides pull off a convincing impersonation act.

Your immune system relies on peptide fragments displayed on cell surfaces to determine what belongs and what does not. These fragments are presented by Major Histocompatibility Complex molecules. When the system works correctly, immune cells recognize harmful invaders and leave healthy tissue alone.

However, in some cases, microbial peptides closely resemble human peptides. When this happens, the immune system may attack both the invader and the body’s own tissues. This phenomenon is a central theory in autoimmune disease research.

Scientists are working to understand how these microscopic imposters succeed. One research team led by Dr. Sanju Singh at the Indian Institute of Technology Bhilai has used molecular simulations to study how bacterial peptides from Klebsiella pneumoniae interact with a specific human immune protein called HLA-B27. This protein has long been associated with autoimmune conditions, particularly Ankylosing Spondylitis.

If peptides can convincingly mimic human fragments, the immune response may become misdirected. Understanding this process at a molecular level could unlock new approaches to diagnosing and managing autoimmune diseases.

So how do researchers study something this tiny and dynamic? They use molecular dynamics simulations, which allow scientists to model how molecules move and interact over time.

The immune system distinguishes friend from foe using proteins known as Major Histocompatibility Complex molecules. In humans, these are referred to as Human Leukocyte Antigens.

HLA-B27 is a variant of MHC Class I molecules. It presents peptide fragments from inside cells to cytotoxic T cells. If a peptide appears foreign, T cells trigger an immune response.

HLA-B27 has a strong association with Ankylosing Spondylitis and related spondyloarthropathies. According to the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, most individuals with Ankylosing Spondylitis carry HLA-B27, although not everyone with HLA-B27 develops disease. This means HLA-B27 increases risk but does not guarantee autoimmunity.

Because HLA-B27 presents peptides to immune cells, researchers suspect that certain microbial peptides may bind in a way that resembles human peptides too closely.

Molecular mimicry occurs when microbial peptides resemble human peptides closely enough to confuse the immune system.

Klebsiella pneumoniae has been studied for decades in connection with HLA-B27-associated autoimmune conditions. This bacterium is commonly found in the gut. Some studies suggest that peptides derived from it may resemble self-peptides and potentially trigger immune activation in genetically predisposed individuals.

It is important to note that molecular mimicry remains a proposed mechanism rather than a fully proven universal cause. Autoimmune diseases are complex and likely involve multiple genetic and environmental factors.

Still, understanding peptide similarity is a major step toward clarity.

Traditional laboratory techniques cannot easily capture every moment of molecular interaction. Molecular dynamics simulations solve this problem by modeling atomic movements over time.

In this research, simulations ran for approximately one microsecond. In molecular terms, this is sufficient to observe meaningful structural fluctuations and binding stability patterns.

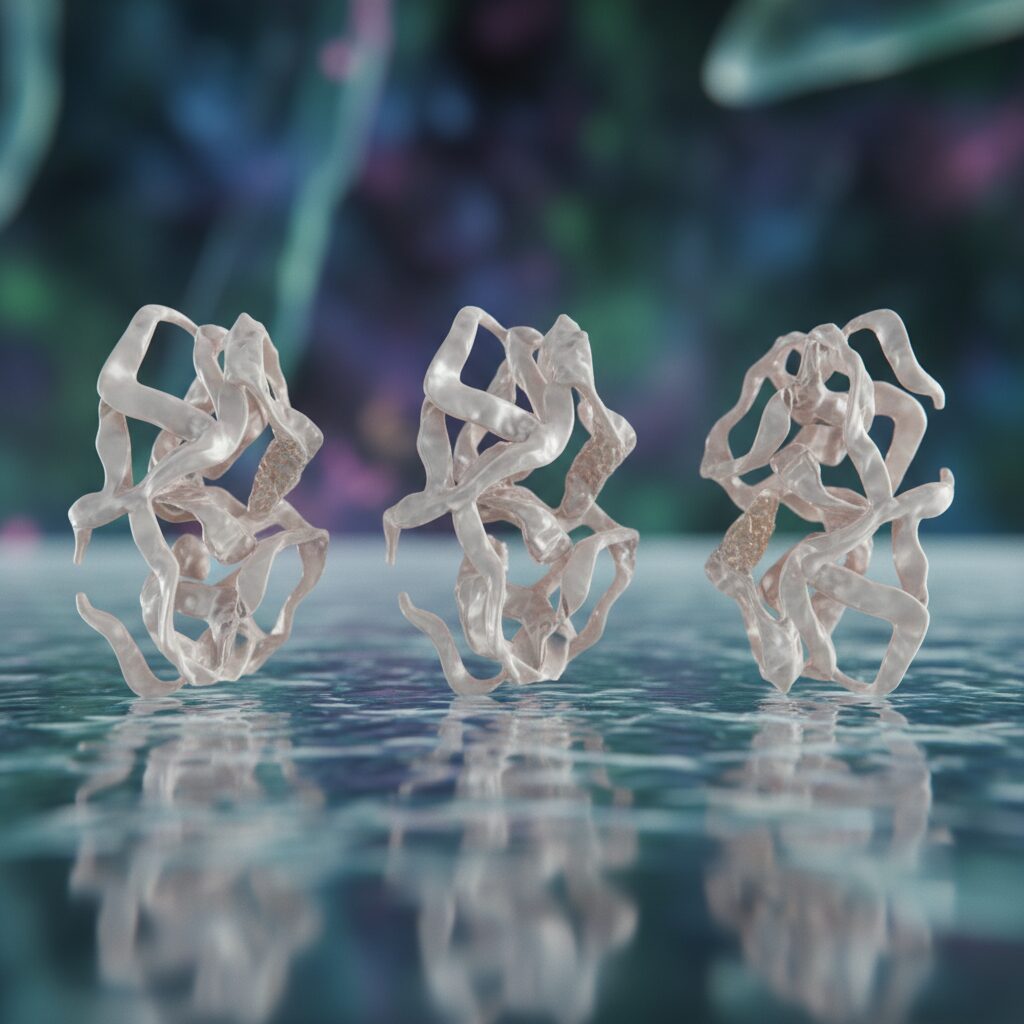

The team analyzed three Klebsiella-derived peptides, labeled KP1, KP2, and KP3, and compared them with a human self-peptide derived from Annexin.

Rather than relying on a single metric, the researchers used a multi-parameter evaluation framework:

This multi-angle analysis reduces bias and increases reliability of conclusions.

KP1 demonstrated structural stability and binding characteristics similar to the human self-peptide. Its hydrogen bonding patterns and free energy calculations suggested stable interaction with HLA-B27.

KP2, by contrast, displayed higher structural deviation and weaker hydrogen bonding patterns, suggesting reduced mimicry potential.

KP3 showed intermediate characteristics, with moderate binding energy and some conformational variability.

Importantly, these results indicate relative mimicry potential within the simulation environment. They do not prove clinical causation. Instead, they identify candidates for further biological validation.

Autoimmune diseases affect millions worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, immune-mediated conditions represent a significant global health burden.

Understanding molecular mimicry could help:

• Identify microbial triggers in genetically susceptible individuals

• Improve diagnostic risk stratification

• Guide vaccine and microbiome research

• Inform therapeutic design targeting peptide presentation pathways

If computational screening can narrow down candidate peptides, researchers can prioritize experimental validation more efficiently.

A critical clarification is necessary.

This research involves computational modeling under controlled scientific protocols. It does not imply therapeutic peptide supplementation or off-label experimentation.

Unregulated peptide products marketed online often lack quality control, verified purity, and clinical oversight. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has repeatedly warned against purchasing unapproved peptide products marketed for research or human use.

Scientific modeling and regulated clinical research are entirely different from grey market peptide sourcing. Responsible translation from research to therapy requires extensive validation.

This study represents a computational foundation. It does not establish definitive causation, but it provides a structured framework for identifying molecular mimicry candidates.

With larger peptide datasets and integrated immunological validation, this approach could:

• Improve early detection strategies

• Refine autoimmune risk profiling

• Support development of peptide-blocking therapeutics

• Enhance understanding of host-microbe interactions

Precision immunology depends on combining genetics, structural biology, and computational modeling. Studies like this help build that bridge.

And yes, peptide adventurers, this is where the real molecular plot twists begin.

What microscopic mystery should we decode next?

All human research MUST be overseen by a medical professional.