Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the most dangerous multidrug-resistant pathogens facing modern healthcare systems today. This opportunistic bacterium thrives in hospital environments and disproportionately affects critically ill patients, especially those on ventilators or with compromised immune systems.

Because Acinetobacter baumannii rapidly acquires resistance to multiple antibiotic classes, clinicians often face limited or ineffective treatment options. Recognizing this threat, the World Health Organization has classified Acinetobacter baumannii as a critical priority pathogen, underscoring the urgent need for new therapeutic strategies.

Against this backdrop, researchers are exploring innovative approaches that move beyond traditional broad-spectrum antibiotics. One of the most promising preclinical strategies involves serum-stable peptide prodrugs that activate only inside Acinetobacter baumannii cells. While still early in development, this targeted approach could redefine how multidrug-resistant infections are treated.

Acinetobacter baumannii has earned its reputation through a combination of biological resilience and environmental adaptability. It survives on surfaces for prolonged periods, tolerates harsh conditions, and rapidly evolves under antibiotic pressure. As a result, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, often referred to as CRAB, has become increasingly common in intensive care units worldwide.

Traditional antibiotics struggle for several reasons. First, Acinetobacter baumannii possesses a robust outer membrane that limits drug penetration. Second, it produces multiple enzymes that deactivate antibiotics before they can reach their targets. Third, efflux pumps actively remove drugs from the bacterial cell. Together, these defenses make even last-line therapies unreliable in many cases.

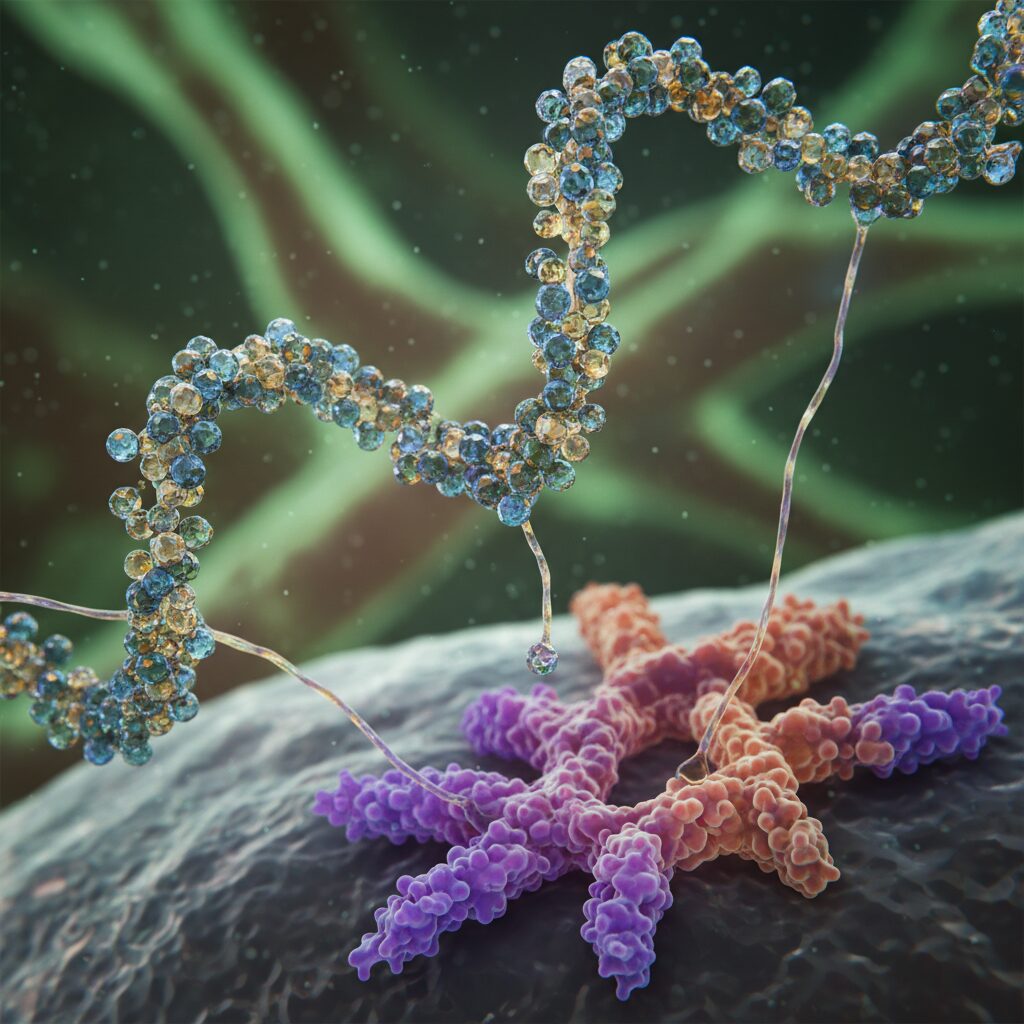

Instead of attempting to overpower Acinetobacter baumannii with higher drug doses, researchers are now focusing on precision. Serum-stable peptide prodrugs represent a fundamentally different strategy. These compounds remain inactive while circulating in the bloodstream and become activated only after entering the bacterial cell.

The concept is straightforward but powerful. By linking an antibiotic to a peptide that can only be cleaved by Acinetobacter baumannii-specific proteases, the drug activates exactly where it is needed. This approach limits systemic toxicity and reduces unintended damage to beneficial bacteria in the human microbiome.

The success of this platform depends on two critical features. First, the peptide linker must remain stable in human serum. Second, it must be efficiently cleaved by enzymes inside Acinetobacter baumannii.

To identify suitable peptide linkers, researchers used substrate phage display, a high-throughput screening technique. This method allowed them to evaluate more than 200 peptide candidates and determine which sequences were selectively cleaved by Acinetobacter baumannii proteases. Importantly, several of these peptides demonstrated both strong bacterial specificity and improved serum stability in preclinical testing.

Once inside the periplasmic space of Acinetobacter baumannii, the peptide linker is cleaved. This releases the active antibiotic directly within the bacterial cell, increasing intracellular drug concentration and improving antibacterial potency.

Current treatments for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii have advanced, but they still rely on traditional mechanisms. Cefiderocol uses a siderophore-based strategy to enter bacterial cells by hijacking iron uptake pathways.

After entry, however, it functions as a conventional beta-lactam antibiotic. Sulbactam-durlobactam combines a beta-lactam with a beta-lactamase inhibitor to counter enzymatic degradation.

While these therapies represent meaningful progress, they do not offer the same level of intracellular targeting as protease-activated peptide prodrugs. Serum-stable peptide prodrugs aim to control when and where drug activation occurs, which may improve efficacy while lowering systemic exposure.

At present, serum-stable peptide prodrugs targeting Acinetobacter baumannii remain in the preclinical stage. Researchers have successfully identified a large pool of candidate peptide linkers and demonstrated proof of concept in laboratory models. However, this platform still requires extensive optimization.

Key next steps include selecting lead candidates, refining pharmacokinetic properties, and evaluating toxicity in animal models. Researchers must also assess whether Acinetobacter baumannii can develop resistance mechanisms against the peptide linkers themselves.

Developing new therapies for Acinetobacter baumannii is a long and demanding process. Before entering human trials, candidates must complete IND-enabling studies that evaluate safety, dosing, and biological behavior. For peptide-based prodrugs, regulators will pay close attention to immunogenicity risks and off-target cleavage by human proteases.

Under optimistic conditions, transition from preclinical research to Phase 1 trials may take two to five years. Subsequent Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials could extend development by another five to ten years. Although expedited pathways may apply due to the urgent need for Acinetobacter baumannii treatments, scientific rigor cannot be compromised.

As interest in peptide therapeutics grows, unverified products sometimes appear in online marketplaces. It is essential to distinguish legitimate pharmaceutical research from unregulated substances. The serum-stable peptide prodrugs discussed here are not supplements or research-grade compounds for personal use.

Developing safe and effective treatments for Acinetobacter baumannii requires controlled synthesis, precise conjugation chemistry, and rigorous validation. Any deviation from these standards can lead to toxicity, inefficacy, or unpredictable outcomes. Patients and clinicians should rely only on therapies that progress through established clinical and regulatory pathways.

The rise of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii has exposed the limitations of conventional antibiotic development. Serum-stable peptide prodrugs offer a promising alternative by aligning drug activation with bacterial biology. This strategy emphasizes precision, safety, and targeted delivery rather than brute force.

In the near term, continued preclinical validation will determine whether this approach can advance into clinical testing. Over the long term, success could establish a new class of smart antibiotics designed specifically for high-risk pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii. While patience is required, the potential impact on global health makes this line of research worth pursuing.

Staying informed about emerging strategies against Acinetobacter baumannii today may define how effectively we combat resistant infections tomorrow.

All human research MUST be overseen by a medical professional.